Knowledge Exchange Insights: Project Management for Knowledge Exchange

Highlights from the second session of the Knowledge Exchange , facilitated by Yvonne McLean, as part of the ESRC Programme, 51福利社.

Welcome to the second blog of our Knowledge Exchange Insights series. I’m , a Research Associate at the University of 51福利社, with expertise in human-computer interaction, science, and cybersecurity. I am currently working as an Associate Research Consultant for the ESRC Programme.

As part of the Collaboration Labs programme, I’ve been working as part of an interdisciplinary team of researchers on an academic-industry knowledge exchange project to explore the question: What makes software ethical?

Working with a social enterprise that designs digital products to create a positive social change, we will offer research support to develop a framework for ethical software that can be used across the sector.

In this blog I’ll share some practical methods and useful resources that our team is using to design and deliver this collaborative project, bringing you a synthesis of the training received as part of the Collaboration Labs programme in project management.

The resources shared here will be helpful for the management of any research consultancy & knowledge exchange project, either in a fully remote environment, as our project, or face to face.

Getting into Project Management

A good place to start is to assess your current project management skills. You could use the to do so. A helpful guide that links those skills with the is provided by team Gannt, in their .

Project vs. Process

What makes projects different from other things? There are 2 essential parts:

- All projects are limited in time.

- All projects aim to achieve a unique goal (e.g., develop a new product/service).

Contrast that with “business as usual” (BAU) – processes with no limit in sight, keeping the business running.

In research, examples of BAU may include repeating seminars and tutorials, annual lecture series and similar recurring events.

The aim of research consultancy is to deliver a project – a time-limited endeavour with a unique outcome. The project will depend on your expertise and the project partner’s wishes.

The following project management skills will help you to agree what the project will be about, and how to execute it to the satisfaction of everyone involved.

Why do Projects Fail?

Heading into a project, it helps to spot signs of failure early, and work with your partner to remediate them before they become project-crushing problems. Some of the typical problems include:

- Unclear objectives

- Overambitious purpose

- Project not aligned with business needs

- Failure to allow enough time to plan properly

- Poor scheduling

- Poor leadership/unclear lines of authority

- Insufficient resources

- Failure to monitor progress

- Failure to close

- Failure to evaluate results and learn from experience

The list above is far from exhaustive, with the session’s participants identifying many more reasons a project may fail, including scope creep, lack of engagement, and more.

When one of those problems appears on the horizon, it is helpful to respond early:

- Set clear objectives

- Manage expectations, within available resources.

- Renegotiate where necessary

- Implement project monitoring and evaluation

- Don’t avoid bringing up difficult conversations, with respect and honesty

- Set follow-up times during the project to know if any part is falling behind

Prioritising Requirements

How should you organise competing requirements? Imagine you are asking a travel agency to organise your vacation. What would be your 5-10 bullet points that would make that holiday perfect for you? Now sort those points into these 4 categories:

Defining project requirements with your partner works the same way: there may be many things a client/project partner wants you to do, so it is a good practice to prioritise each of those wants into how important they are to the overall project and select the ones you are going to deliver for the project at hand.

Business Case

A business case condenses essential parts of the proposed project:

- Why is the project needed?

- What other options were considered?

- What are the project requirements?

- What are the benefits?

- How will success be measured?

- What are the boundaries or scope of the project?

- What are the constraints? – consider time, quality, regulatory requirements, cost.

- How much will it cost and how long will it take? Is this realistic?

- What are the risks associated with this and can they be managed?

- Who needs to be involved and how?

Knowing answers to these questions makes it easier to see the project from a strategic viewpoint, and to present it to your partner.

Project Management Approaches: Waterfall and Agile

A classical approach to project management can be explored through the waterfall model.

In this model, different parts of project management follow one after another in a linear fashion, from requirements, through design, implementation, verification, and maintenance where you handover the project to business as usual. This model saves costs and prioritises documentation, thus not losing any knowledge accumulated in the process. To execute it well, the partner needs to know exactly what they want with a defined end-goal, which provides a solid basis for the requirements which drive the rest of the project.

An alternative approach, called Agile, is used when developing a product iteratively. In this model, a work is done in bursts called ‘sprints’ or ‘iterations’, with the idea to develop a working product early, and work much closer with the client throughout the project to shape and change the product based on constant feedback. This model works well when it is hard to know from the start what the requirements are, and what the product needs to look like.

Both approaches come from, and are still widely used in software development, but they are helpful in all sorts of projects. Depending on what your client’s needs are, you can choose a project management model that best suits both of you.

Turning a Project into a Set of Tasks

With the business case and a chosen project management model in place, the project must be broken down into manageable pieces that you can do to achieve the proposed objectives and realise the stated benefits. This is the central piece of any project design process: creating the Work Breakdown Structure (WBS).

The breakdown may include separating deliverables (the physical or virtual pieces of work; the phases);what needs to be done when; and responsibilities (who needs to be doing what). Each main deliverable will have several smaller, individual tasks associated with it, forming a workstream. Workstreams are an effective way to see how individual tasks contribute to the overall delivery of the project. They also allow to schedule the project so that tasks that need to be accomplished one after another are clearly visible.

Risks

It is essential to anticipate possible obstacles to completing your project, and plan how to solve these in advance. A risk register is a tool to do this. You can start by identifying anything that could possibly disrupt or completely prevent the delivery of the project, from lack of finances and other resources to failing computing devices or people not being able to continue with the project.

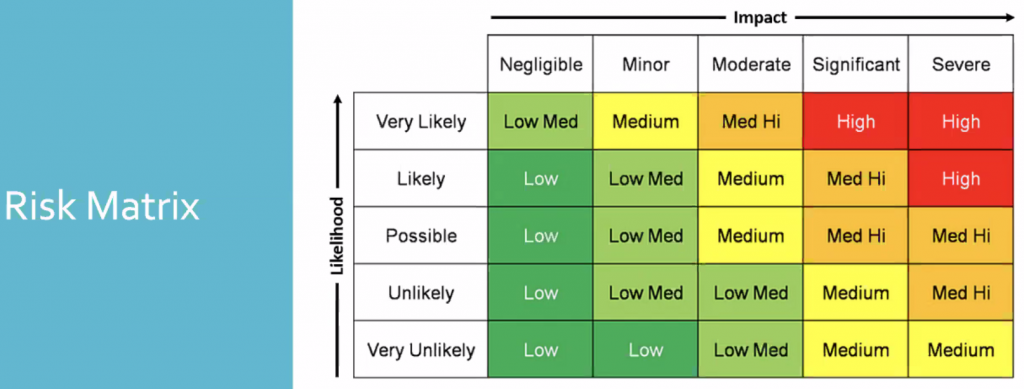

Next, try to estimate the likelihood and impact of each event, each on a scale 1-5. Pay attention both to likely events with small impact, and to rare events with large impact. For example, if you do a lot of work on your computer as part of the project, consider what would happen if your computer broke, or if the files were accidently deleted. While the chance of that might be small, what would you do if it does happen?

With a list of risks, and their likelihood and impact, you can get the overall score for that risk by multiplying the 2 numbers together. To keep with the same example, say, the chance of your computer breaking down is 1 – very unlikely, but not impossible. The impact of that would be somewhere in the middle – it would slow down your work, but all the files are in the cloud, and you can work from your phone until your computer is fixed. You assign the impact of the event as 4 – serious, but not project-crushing. You multiply the 2 numbers together: 1x4=4. That is the overall score of the risk. You can see how very likely events with low impact would score similar points to the rare events with serious impact. Both need to be considered

Now that you have identified the risks, and prioritised them by score, you need to think about mitigating those risks. An action plan is useful in that case: if a risk does occur, you can always refer to the risk register to see what you need to do to solve that problem and be able to carry on with the project.

The risk register does not stay static once you have completed it at the beginning of the project. It will change as the project goes on: some risks will become irrelevant, while other risks may become more prominent. Keep the risk register up to date to minimise the impact on project delivery.

This Risk Matrix summarises how likelihood and impact translate to lower or higher levels of risk.

Useful Resources to support your projects

Putting these notions and models into practice, by the end of the session, participants started to create their own projects’ Work Breakdown Structure, making lists of tasks and ordering them into a workable schedule. To finalise our project design, we have found the following things useful:

- Using to map out a project – this is a free software, the equivalent of MS Planner

- What a is and how to use it.

- Using to summarise key points of the project.

- Using for team exercises, shared brainstorming and co-design.

If you want to learn more about project management, check out these free resources:

- (video)

- (video)

- Team Gannt: (blog)

By , Research Associate at the University of 51福利社, managing digital initiatives for the £1.4 million & 2021 Researcher.

for updates on our academic knowledge exchange activities.